Although the brain tissue has a consistency somewhat like jello, soft and squishy, palaeontologists discovered an intact brain in a 310 million-year-old fossil. Brain tissue is rich in fat, which means it should rot quickly; however, it did not.

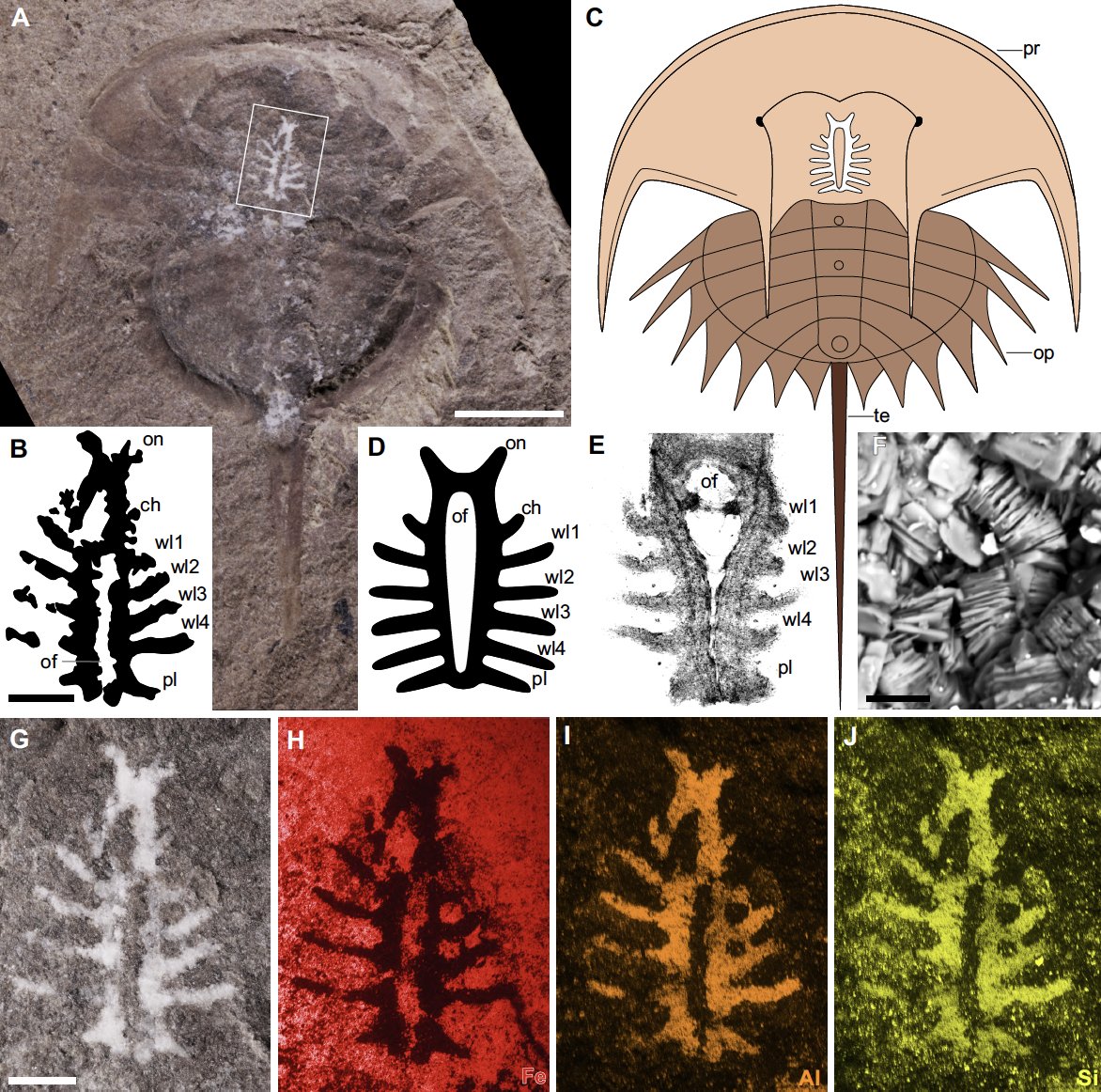

Russell Bicknell, an invertebrate palaeontologist at the University of New England in Australia, found a rare imprint of the brain and other nervous system bits in a fossilized horseshoe crab body. Found in the Mazon Creek deposit in northeastern Illinois, this is the first discovery of a preserved brain that dates over 300 million years back.

“These kinds of fossils are so rare that if you happen to stumble upon one, you’d generally be in shock,” said Bicknell. “We’re talking a needle-in-a-haystack level of wow.”

Brain tissue preservation

The preserved horseshoe crab brain helps experts see the evolution of arthropod brains. However, the report shows minor changes over hundreds of millions of years. Compared to the previous brain tissues found, the preservation of the horseshoe crab brain is very different.

The penny-size horseshoe crab was buried in what used to be a shallow, brackish marine basin over 300 million years ago. The creature’s body was quickly covered up by Siderite, a mineral composed of iron carbonate encasing it in mould. Although the soft tissue started to decompose, kaolinite, a white clay mineral, took the brain’s place. Bicknell found the exceptionally preserved brain thanks to the white cast on a dark-grey rock.

“This is a completely different mode of brain preservation,” said Nicholas Strausfeld, a neuroanatomist at the University of Arizona. He was among the first to report a fossilized arthropod brain in 2012. “It’s remarkable.”

Scientists also hope to find more examples from the Mazon Creek deposit.

“If there is one, there have to be more,” said Javier Ortega-Hernández, an invertebrate palaeontologist at Harvard University’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and the study’s co-author.

Leave a Reply